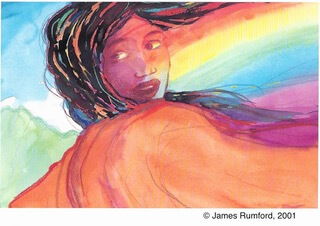

Kahalaopuna

A Legend of the Valley of the Rainbow as told by HRH David Kalākaua (The Legends and Myths of Hawaii, 1888)

Manoa is the most beautiful of all the little valleys leaping abruptly from the mountains back of Honolulu and cooling the streets and byways of the city with their sweet waters. And it is also the most verdant. Gentle rains fall there more frequently than in the valleys on either side of it, and almost every day in the year it is canopied with rainbows. Sometimes it is called, and not inappropriately, the Valley of Rainbows.

Why is it that Manoa is thus blessed with rains, thus ornamented with rainbows, thus cradled in everlasting green? Were a reason sought among natural causes, it would doubtless be found in a favoring rent or depression in the summit above the valley and overlooking the eastern coast of Oʻahu, where wind and rain are abundant. But tradition furnishes another explanation of the exceptionally kind dealings of the elements with Mānoa – not as satisfactory, perhaps, as the one suggested but very much more poetic.

Far back in the past, as the story relates, the projecting spur of Akaaka, above the head of Mānoa Valley, was united in marriage with the neighboring promontory of Nalehuaakaaka. A growth of lehua bushes still crowns the spur in perpetual witness born – a boy named Kahaukani, which signified Manoa wind, and a girl called Kauahuahine, which implied Manoa rain. At their birth, they were adopted by a chief and chiefess whose names were Kolowahi and Pohakukala. They were brother and sister, and cousins, also, of Akaaka. The brother took charge of the boy, and the sister assumed custody and care of the girl. Reared apart from each other, and kept in ignorance of their close relationship, through the management of their foster parents they were brought together at the proper age and married. The fruit of this union was a daughter, who was given the make Kahalaopuna, and who became the most beautiful woman of her time. Thus it was that the marriage of the Wind (Kahaukani) and Rain (Kauahuahine) of Mano brought to the valley as an inheritance the rainbows and showers for which it has been distinguished.

To continue the story of the ancient bards of Oʻahu, Kahalaopuna – or Kaha, as the name will hereafter be written – grew to a surpassingly beautiful womanhood. A house was built for her in a grove of sandal-trees at Kahaiamano, where she lives with a few devoted servants. The house was embowered in vines, and two poloulou, or tabu staves, were kept standing beside the entrance, to indicate that they were guarded from intrusion by a person of high rank. Her eyes were so bright that their glow penetrated the thatch of her hale, and a luminous glimmer played around its openings. When bathing a roseate halo surrounded her, and a similar light is still visible, it is claimed, when her spirit revisits Kahaiamano.

In infancy, Kaha was betrothed to Kauhi, a young chief of Kailua, whose parents were so sensible of the honor of the proposed union that they always provided her table with poi of their own making and choice fish from the ponds of Kawainui. The acceptance of these favors placed her under obligations to the parents of Kauhi and kept her in continual remembrance of her betrothal. Hence she gave no encouragement to the many chiefs of distinction who sought to obtain glimpses of her beauty and annoyed her with proffers of marriage. The chief to whom she was betrothed was, like herself, of something more than human descent, and she felt herself already bound to him by ties too sacred to be broken.

The fame of her beauty spread far and near, and people came from long distances to catch glimpses of her from lands adjoining, as she walked to and from her bathing pool or strolled in the shelter of the trees surrounding her house. Among those who many times approached her dwelling but failed to see her were Keawaawakiihelei and Kumauna, two inferior chiefs, whose eyes were disfigured by an unnatural distention of the lower lids. In ungenerous revenge, and envious of those who had fared better, they decked themselves with leis of flowers, and, repairing to the bathing place at Waikiki, boasted that the garlands had been placed around their necks by the beautiful Kaha, with whom they affected the greatest intimacy.

Among the bathers at that popular spot was Kauhi. Although the day fixed for his marriage with Kaha was near at hand, he had never seen her – this being one of the conditions of the betrothal. The stories of the two miscreants were repeated until Kauhi at length gave them credence, and in a fit of jealous fury he resolved to kill the beautiful enchantress who had thus trifled with his love.

Leaving Waikiki in the morning, he reached Kahaiamano about midday. Breaking from a pandanus tree, a heavy cone of nuts with a short limb attached, he presented himself at the house of Kaha. She had just awoken from a nap, and was about to proceed to her bathing pond when she was startled at observing a stranger at her door. He did not speak, but from frequent descriptions, she at length recognized him as Kauhi, and with some embarrassment invited him to enter. Declining, and admitting his identity, he requested her to step without, and she unhesitatingly complied. His first intention was to kill her at once, but her supreme loveliness and ready obedience unnerved him for the time, and he proposed that she should first bathe and then accompany him in a ramble through the woods.

To this she assented, and while she was absent Kauhi stood by the door, moodily watching the bright light playing above the pond where she was bathing. He was profoundly impressed with her great beauty and would have given half the years of his life to clasp her in his arms unsullied. The very thought intensified his jealousy; and when his mind reverted to the disgusting objects upon whom he believed she had bestowed her favors, he revoked to shower her no mercy, and impatiently awaited her return.

Finishing her bath and rejoining him at the door, her beauty was so enrapturing that he was afraid to look at her face, lest he might again falter; it was therefore with his back turned to her that he declined to partake of food before they departed, and motioned her to follow him. His actions were so strange that she said to him, half in alarm:

“Are you, indeed, angered by me? Have I in any way displeased you? Speak that I may know my fault!”

“Why, foolish girl, what could you have done to displease me?” replied Kauhi, evasively.

“Nothing, I hope,” returned Kaha; “yet your look is cold and almost frightens me.”

“It is my mood to-day, perhaps,” answered Kauhi, increasing his pace to give employment to his thoughts; “you will think better of my looks, no doubt, when we are of longer acquaintance.”

They kept on together, he leading and she following, until they reached a large rock in Aihualama, when he turned abruptly, and, seizing the girl by the arm, said:

“You are beautiful – so beautiful that your face almost drives me mad; but you have been false and must die!”

Kahaʻs first thought was that he was making sport with her; but when she looked up into his face and saw that it was stern and smileless, she replied:

“If you are so resolved upon my death, why did you not kill me at home, so that my bones might be buried by my people? If you think me false, tell me with whom, that I may disabuse your mind of the cruel error possessing it.”

“Your words are as fair as your face, but neither will deceive me longer!” exclaimed Kauhi; and with a blow on the temple with the cone of hala nuts, which he was still carrying, he laid her dead at his feet. Hastily digging a hole beside the rock, he buried the body and started down the valley toward Waikiki.

He had scarcely left before a large owl – a god in that guise, who was related to Kaha and had followed her – unearthed the body, rubbed his head against the bruised temple, and restored the girl to life. Overtaking Kauhi, Kaha sang behind him a lament at his unkindness. Turning in amazement, he observed the owl flying above her head and recognized the power that had restored her to life.

Again ordering Kaha to follow him, they ascended the ridge dividing the valleys of Manoa and Nuuanu. The was beset with sharp rocks and tangled undergrowth, and when Kaha reached the summit her tender feet were bleeding and her pau was in tatters. Seating herself on a stone to regain her breath, with tears in her eyes she implored Kauhi to tell her whether he was leading her and why he had sought to kill her. His only reply was a blow with the hala cone, which again felled her dead to the earth. Burying the body as before he resumed his way toward Waikiki.

Again flying to the rescue of his beautiful and sinless relative, the owl-god scratched away the earth above her and restored her once more to life. Following Kauhi, she again chanted a song of lament behind him and begged him to be merciful to one who had never wronged him, even in thought. Hearing her voice, he turned, and without answer conducted her across the valley of Nuuanu to the ridge of Waolani, where he killed and buried her as he had done twice before, and the owl-god a third time removed the earth from the body and gave it life.

She again overtook her merciless companion and again pleaded for life and forgiveness for her unknown fault. Instead of softening his heart, the words of Kaha enraged him, and he resolved not to be thwarted in his determination to take her life. Leading her to the head of Kalihi valley, where she was for the fourth time killed, buried, and resurrected as before, he next conducted her across plains and steep ravines to Pohakea, on the Ewa slope of the Kaala mountains. He hoped the owl-god would not follow them so far, but, looking around, he discovered him among the branches of an ohia tree not far distant.

As Kaha was worn down with fatigue, it required but a slight blow to kill her the fifth time, and when it was dealt to the unresisting girl her body was buried under the roots of a large koa tree, and there left by Kauhi, satisfied that it could not be reached by the owl-god. Repairing to the spot after the departure of Kauhi, the owl put himself to the task of scratching the earth from the body; but his claws became entangled with the roots, which had been left to embarrass his labors, and, after toiling for some time and making little or no progress, he abandoned the undertaking as hopeless, and, reluctantly left the unfortunate girl to her fate, following Kauhi to Waikiki.

But there had been another witness to the many deaths of Kaha. It was a little green bird that had flitted along unobserved either by Kaha or her companion and had followed them from Kahaiamano, flying from tree to tree and making no noise. Noting with regret that the owl-god had abandoned the body of Kaha, the little bird, which was a cousin to the girl and a supernatural being, flew with haste to the parents of Kaha and informed them of all that had happened to their daughter.

The girl had been missed, but as some of her servants had recognized Kauhi, and had seen her leave the house with him, her absence occasioned no uneasiness; and when the little green bird, whose name was Elepaio, recounted to the parents the story of Kaha’s great suffering and many deaths, they found it difficult to believe that Kauhi could have been guilty of such fiendish cruelty to the radiant being who was about to become his wife. They were convinced of Elepaio’s sincerity, however, and with great grief prepared to visit the spot and remove the remains of Kaha for more fitting internment.

Meantime the spirit of the murdered girl discovered itself to Mahana, a young chief of good address, who was returning from a visit to Waianae. Directed by the apparition, he proceeded to the koa tree, and, removing the earth and roots, discovered the body of Kaha. He recognized the face at once, notwithstanding the blood and earth stains disfiguring its faultless regularity. He had seen and become enraptured with its beauty at Kahaiamano, and on one occasion, which lived in his memory like a beautiful dream, he had been emboldened by his love to approach sufficiently to exchange modest words and glances with it.

Gently removing the body from the shallow pit in which it had been buried, Mahana found to his great joy that it was still warm. Wrapping it in his kihei, or shoulder scarf, and covering it with maile ferns and ginger, he tenderly bore it in his arms to his home at Kamoiliili. As he walked he chanted his love and scarcely felt his burden. Reaching home, he laid the body upon a kapa-moe, and earnestly implored his elder brother to restore it to life, he being kahuna and having skill in such matters.

Examining the body and finding that he could do nothing unaided, the brother called upon their two spirit-sisters for assistance, and through their instrumentality, the soul of Kaha was once more restored to its beautiful tenement. But it was some time before she fully recovered from the effects of her cruel treatment – some time, in fact, before she was able to walk without support. In her convalescence, Mahana was her considerate and constant companion and found no greater pleasure in providing her with the delicacies to which she had been accustomed. She was greatly benefited by the waters of the underground cave of Mauoki, to which she was frequently and secretly taken, and under the watchful care of Mahana she was at length restored to health.

II

With her recovery, in the home of her new friends at Kamoiliili, Kaha was introduced to a life that was new to her; but it was by no means an unpleasant change from the restraints of her listless and more sumptuous past behind the protecting shadows of the puloulous, where she was jealously watched, and where rank closed her doors to congenial companionship. She repaired to an unfrequented beach, and, unobserved, played with the shifting sands and sang to the waves, and at night went with Mahana to the reef with torch and spear in search of fish and squid.

Knowing that her restoration to life could not be long kept from her relatives, Mahana told her that his love for her was great, and asked her to become his wife.

“I shall never love anyone better than Mahana,” replied Kaha; “but from infancy I have been betrothed to Kauhi; my parents, the Wind and the Rain of Manoa, have promised that I shall be his wife, and while he lives I can be the wife of no other.”

The argument that Kauhi had forfeited all right to her by his cruelties failed to share her resolution, and the brother of Mahana advised him to in some manner compass the death of Kauhi. To this end, they appraised the parents of Kaha of her restoration to life and conspired with them to keep the information secret for a time. This they were the more disposed to do because of their uncertainty concerning what Kauhi might again attempt should he find the girl alive.

In pursuance of the plan adopted, Mahana learned from Kaha all the songs she had chanted to mollify the wrath of Kauhi while she was following him through the mountains and then sought the kilu houses of the king and chiefs in the hope of encountering his rival. It was not long before they met, under just such circumstances as Mahana desired. He discovered Kauhi engaged with others in a game of kilu, and joined the party as a player. The kilu passed from the hand of Kauhi to Mahana, who, on receiving it, began to chant the first of Kaha’s songs.

Surprised and embarrassed, Kauhi, in violation of the rules of the game, stopped the player to inquire where he had learned the words of the song he was singing. The answer was that he had learned them from Kaha, the noted beauty of Manoa, who was a friend of his sister, and was then visiting them at their home. Knowing that she had been deserted by the owl-god, and feeling assured that Kaha was no longer living, Kauhi denounced as a falsehood the explanation of the player. Bitter words followed, and but for the interference of friends there would have been bloodshed.

They met the next day at the kilu house, and in the evening following, when similar scenes occurred between Mahana and his rival, Kauhi became so enraged at length that he admitted that he had killed the beautiful Kaha of Manoa, and declared the Kaha of Mahana to be an imposter, who had heard of the death of the real Kaha and audaciously assumed her name and rank. He then challenged Mahana to produce the woman claiming to be Kaha, agreeing to forfeit his life should she prove in flesh and blood to be the one whom he knew to be dead, and subjecting Mahana to a like penalty in the vents of the claimant proving to be other than the person he represented her to be.

It had been the purpose of Mahana to provoke his rival to a combat with weapons, but the challenge of Kauhi presented itself as a more satisfactory means of accomplishing the object of his aim, and he promptly accepted it; and, that both might be more firmly bound to its conditions, they were repeated and formally ratified in the presence of the king and principal chiefs of the district.

The day fixed for the strange trial arrived. It was to be in the presence of the king and a number of distinguished chiefs, and Akaaka, the grandfather of Kaha, had been selected as one of the judges. Imus had been erected near the sea-shore by the respective friends of the contestants, in which to roast alive the vanquished chief, and dry wood for the heating was piled beside them.

Fearing that the spirit of the murdered girl might be able to assume a living appearance, and thus impose upon the judges, Kauhi has consulted the priests and sorcerers of his family. and was advised by Kaea to have the large and tender leaves of the ape plant spread upon the ground where Kaha and her attendants before the tribunal were to be seated. “When she enters,” said the laula, “watch her closely. If she is of flesh her weight will rend the leaves; if she is merely a spirit the leaves where she walks and sits will not be torn.”

On her way to Waikiki, the place designated for the trial, Kaha was accompanied by her parents, friends, and servants, and also by the two spirit-sisters of Mahana, who had assumed human forms in order to be better able to advise and assist her, if occasion required. They informed her of Kaea’s proposed test with ape leaves and advised her to quietly tear and rend them as far as possible for some distance around her, in order that the spirit-friends beside her, who would be unable to do as much for themselves, might thereby escape detection. If discovered, they would be exposed to the risk of being killed by the poe-poi-uhane, or spirit-catchers.

Arriving at Waikiki, Kaha and her companions repaired to the large enclosure in which the trial was to take place, the king, chiefs, judges, and advisers of Kauhi were already there, and thousands of spectators were assembled in the grounds adjoining. The ape leaves had been spread, by the consent of the king, as advised by Kaea, and Kaha entered with her friends and advanced to the place reserved for them. not far from her stood Kauhi. As he bent forward in anxiety and looked into her star-like eyes, with a sinking heart he saw that their reproachful gleam was human, and knew that he had lost the wager of his life.

Observing her instructions, Kaha took pains to quietly rend and rumple the ape leaves under and around her. So far as she was concerned, the test was satisfactory. The evidence of the leaves torn by her feet could not be questioned. Kaea was therefore compelled to admit that Kaha was a being of flesh and bone; but in his disappointment, he declared that he saw and felt the presence of spirits in some manner connected with her, and would detect and punish them.

Irritated at the malice of the kaula, Akaaka advised him to look for the faces of the spirits in an open calabash of water. Eagerly grasping at the suggestion, Kaea ordered a vessel of clear water to be brought in, and incautiously bent his eyes over it. He saw only the reflection of his own face. Akaaka also caught a glimpse of it, and, knowing it to be the spirit of the seer, he seized and crushed it between his palms, and Kaea fell dead to the earth beside the calabash into which he had been peering.

Akaaka then turned and embraced Kaha, acknowledging that she was his granddaughter and that her purity and obedience rendered her worthy of the love of the bold upland of Akaaka and of her parents, the Wind and Rain of Manoa.

The curiosity of the king was aroused, and he demanded an explanation of the strange proceedings he had just witnessed. Kaha told her simple story, and Kauhi, on being interrogated, could deny no part of it. As an excuse for his barbarous conduct, however, he repeated and attributed his jealous rage to, the boastful assertions of Kumauna and Keawaawakiihelei. The slanderers were sent for at once, and, on being confronted by Kaha, admitted that they had never seen her before and that they had boasted of their intimacy with her to make others envious of their good fortune.

“Well,” replied the king, after listening to the confessions of the miscreants, “as your efforts in exciting the envy of others have brought terrible suffering to an innocent girl, I now promise you something of which no one, I think, will envy you. You will be baked alive with Kauhi! If you have friends among the gods, pray to them that the imus may be hot and your sufferings short!”

The imus were ordered to be heated at once, and Kauhi and the two calumniators were thrown into them alive and roasted. The first went to his death bravely, chanting a song of defiance as he proceeded to the place of execution, but the others vainly struggled and sought to escape. The retainers of Kauhi were so disgusted with his cruelty to Kaha that they transferred their allegiance to her, and the lands and fishing rights that had been his were given to Mahana at once.

“And how do you intend to reward the young chief who hazarded his life for you?” inquired the king, pleasantly addressing Kaha as he rose to depart.

“With my own, O king!” replied the girl, advancing to Mahana and laying her head upon his breast.

“So shall it be, indeed,” returned the king. “I have said it, and you are now the wife of Mahana.”

In his gratitude, the happy young chief threw himself at the feet of the king and said:

“I am your slave, great king! Demand of me some great service or sacrifice, that you may know that I am grateful!”

“Even as you desire,” returned the king, “ I will put you to a task that will tax to the utmost your patience.”

“I listen, O king!” said Mahana, resolutely.

“The sacrifice I ask,” resumed the king, with a merry twinkle in his eye, “ is that for three full days from this time you embrace not your bride.”

“A sacrifice, indeed!” exclaimed Mahana, catching the kindly humor of the request, and slyly glancing at the downcast face of Kaha. “It is–”

“Too great, I see, for one whose beard is not yet fully grown,” interrupted the king. “Well, I withdraw the request. The girl is yours; take her with you without conditions!”

———-

Here the story of the trials of Kaha should end; but it does not. Some time during the night following the death of Kauhi a tidal wave, sent by a powerful shark-god, swept over and destroyed the imus in which the condemned men had been roasted, and their bones were brought out to sea. Through the power of their family gods Kumauna and Keawaawakiihelei were transformed into two peaks in the mountains back of Manoa Valley while Kauhi, who was distantly related to the shark-god, was turned into a shark.

For two years Kaha and her husband lived happily together, surrounded by many friends and enjoying every comfort. Her grandfather Akaaka, visited her frequently, and, knowing of Kauhi’s transformation and vindictive deposition, admonished her to avoid the sea. For two years she heeded the warning; but one day, when her husband was absent and her mother was asleep, she ventured with one of her women to the beach to witness sports of the bathers and surf-riders. As no harm came to the swimmers, and the water was inviting, she finally borrowed a surf-board, and, throwing herself joyfully into the waves, was carried beyond the reef.

This was the opportunity for which Kauhi had long waited. Seizing Kaha, and biting her body in twain, he swam around with the head and shoulders exposed above the water, that the bathers might note his triumph. The spirit of Kaha at once returned to the sleeping mother and informed her of what had befallen her daughter. Waking and missing Kaha, the mother gave the alarm, and with others immediately proceeded to the beach. The bathers, who had fled from the water on witnessing the fate of Kaha, confirmed the words of the spirit, and canoes were launched in pursuit of the shark, still exhibiting his bloody trophy beyond the reef.

Swimming with the body of Kaha just far enough below the surface to be visible to the occupants of the canoes, the monster was followed to Waianae, wherein shallow waters he was seen, with other sharks, to completely devour the remains. This rendered her restoration to life impossible, and the pursuing party sadly returned to Waikiki.

With the death of Kaha her parents relinquished their human lives and retired to Manoa Valley. The father is known as Manoa Wind, and his visible form is a small grove of hau trees below Kahaiamano. The mother is recognized as Manoa Rain, and is often met within the vicinity of the former home of her beloved and beautiful daughter.

The grandparents of Kaha also abandoned with human forms, Akaaka resuming his personation of the mountain spur bearing his name, and his august companion nestling upon his brown in the shape of a thicket of lehua bushes. And there, among the clouds, they still look down upon Kahaiamano and the fair valley of Manoa, and smile at the rains of Kauahuahine, which day by day renew their beauty, and keep green with ferns and sweet with flowers the earthly home of Kahalaopuna.