Making Dye from Native & Canoe Plants

By Zoe Welch

By Zoe Welch

Zoe Welch lives in Pālolo Valley and is a ninth-grader at Punahou School. For her Biology “Action Aloha ‘Āina” semester project, she was tasked with creating an ecology project that promotes awareness, appreciation, and knowledge of Hawaiʻi and honors the intersection of culture, history, and ecology. She chose to make dye from Native and Canoe plants because she likes working with nature and making useful things out of natural elements. She also knew next to nothing when it came to making dye with plants. After having researched the subject and completed her project, she wants to let everyone know how fun it was and what these plants look like so you can identify them too.

Full disclosure – Zoe is the daughter of MHC’s Executive Director and they worked together to find the plants and experiment with dyes. They discovered that ʻilima papa flowers and akia bark don’t produce dye. Zoe is lucky to have plant-loving aunties who could tell her where to find these special flowers.

ʻOlena

Hau

Kokiʻo ʻUla

Maʻo

ʻŌlena (Canoe Plant)

ʻŌlena has been used for its medicinal, nutritional, and dyeing properties since ancient times by numerous peoples. Originating in India and Indonesia, it was brought to Hawaiʻi by Polynesians in their canoes (that’s why it’s called a canoe plant). With its name coming from the Hawaiian word for ‘yellow,’ ʻōlena is revered for its mana (life force or spiritual power) and used to cleanse and purify people, physical spaces, and objects. Ancient Hawaiians held the belief that ‘you are what you eat,’ so the fact that we can dye our clothes and make medicine from this plant is something very special. Nurturing a plant, giving it water, and using it to provide for your family is not practiced today as it was then.

Part of the ginger family ʻōlena grows to about three feet above the ground, with rhizomes that are found underground. The rhizome is what we use for cooking, medicine and to make dye. Above the ground, it’s easy to confuse the leaves with ‘awapuhi.

Supplies:

- ʻŌlena roots (If you don’t have any growing, store-bought is fine)

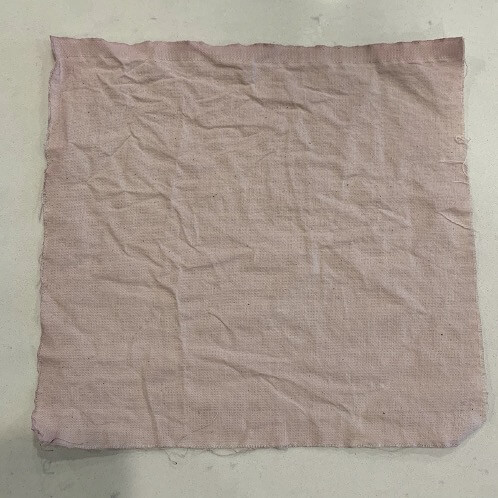

- Muslin or other cloth to dye

- Spice grinder, food processor, or blender

- Mortar and pestle

- Baking pan

- Parchment paper

- Pot

- Cooling rack (for drying cloth)

*CAUTION – ʻŌlena stains anything and everything!

** Note – Dye will vary in color depending on the maturity of the rhizomes. Younger roots will make a pale yellow while older roots make a darker golden yellow-orange.

Making ʻŌlena Powder

Preheat oven to the lowest temperature setting possible (usually around 200º)

Wash ʻōlena thoroughly and slice into discs between 1/8 to 1/4 inch thick.

Lay the slices on a parchment-lined baking sheet & bake for 1.5 hours or until you can break the slices in half with your fingers.

Let the ʻōlena cool a little, then use a food processor, spice grinder, or blender to grind the dried slices. Get any lumps out with a mortar and pestle.

Sift powder to remove larger grains. You will be left with a fine ʻōlena powder.

Dyeing the Cloth

Mix 1 tablespoon of ʻōlena powder with 2 cups of water in a pot or bowl and let your cloth sit in the dye for several hours, until you are satisfied with the color (I let my muslin sit for 5+ hours).

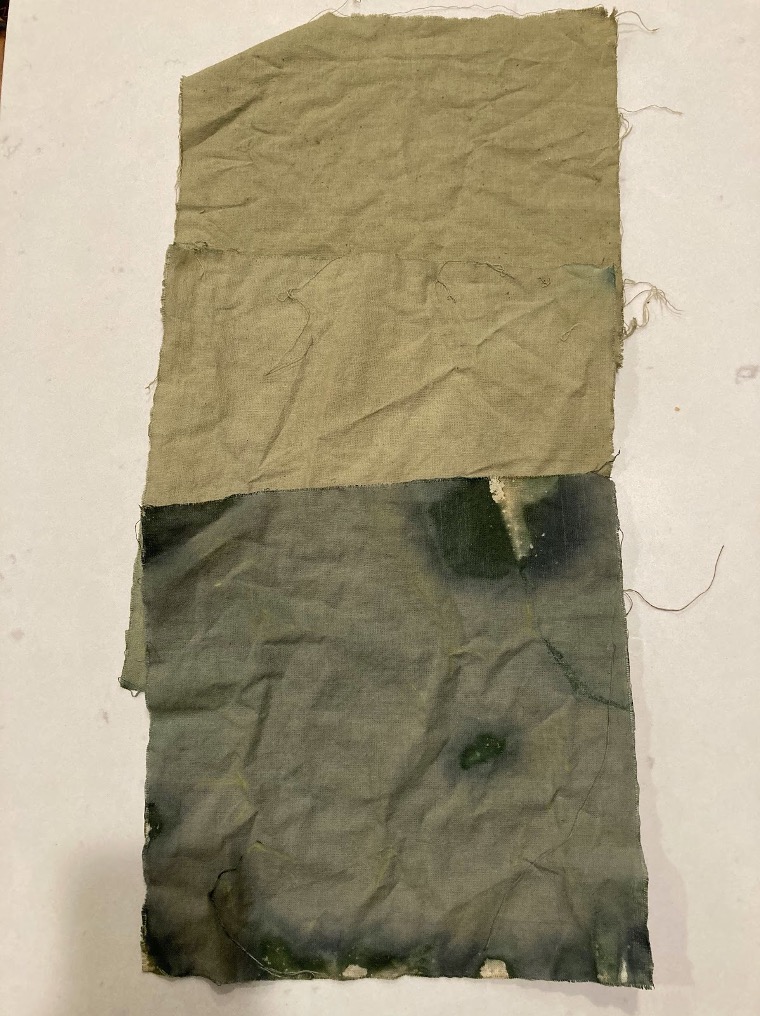

Dry on a drying rack or cooling rack and you will have a beautiful yellow cloth.

Hau (Canoe Plant)

“One Hawaiʻi legend says that hau is a sister of the goddess Hina, changed into a tree. The people of Tahiti say hau is the grandchild of heaven and earth. Some people equate the brief span of the hau flower as representative of the transitory nature of human life.” – Canoe Plants of Ancient Hawai’i

Hau, or sea hibiscus (Hibiscus tiliaceus), had many uses. Its wood was used to make canoe outriggers, fishnet floats, and start fires while the young bark was used for cordage (ʻili hau). The bright yellow flowers have reddish centers and as the day goes by, their color changes to orange and then reddish-brown. These flowers are used to make dye, but the plant as a whole has many medicinal properties. The flowers were used as a laxative, the buds chewed and eaten for a dry throat, and slime from soaking the bark of the stems cured congested chests. The tree provides good shade and is often used as a landscaping element (such as those above the walkway at Kaimana Beach). In ancient times, hau was so highly valued that permission to cut it was required from the village chief.

Supplies

- Hau flowers

- Cloth to dye

- Pot

- Bowl

- Colander or strainer

- Cooling rack

Instructions

Collect hau flowers.

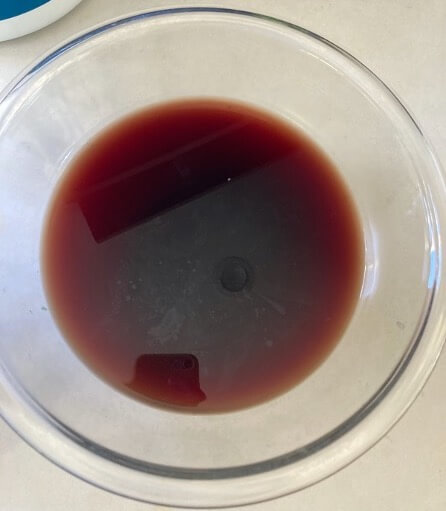

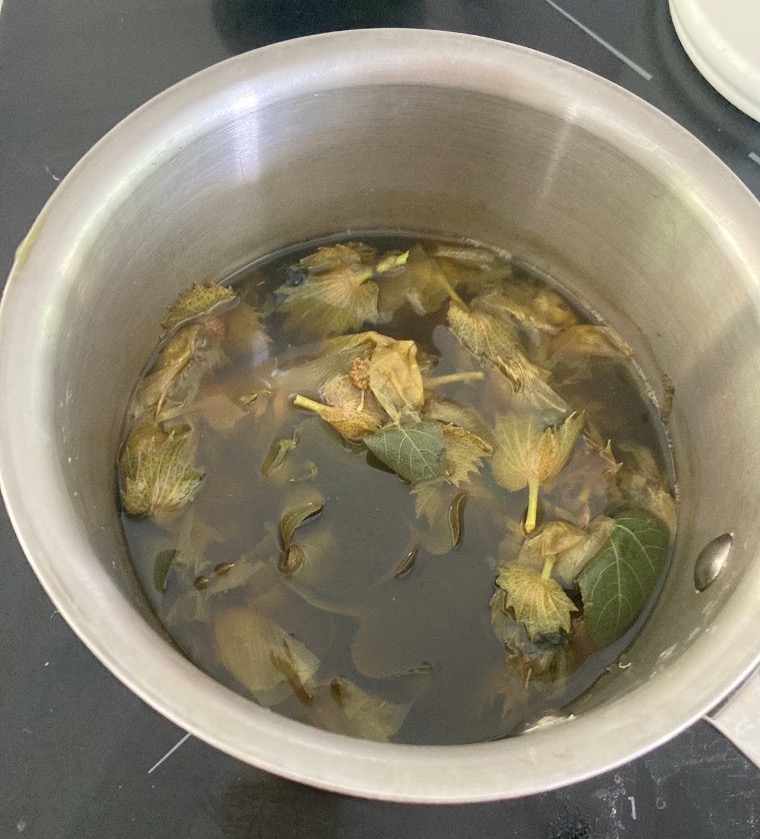

Place 30 or so flowers into a pot of water and bring to boil. Let them sit until all the color is leached from flowers (the petals should be dull to greyish in color).

Pour the cooked flowers into a strainer over a bowl, making sure to squeeze flowers to get excess dye out.

Let the cloth sit in the dye for 5+ hours. After soaking, run fabric under some water to wash out the gooeyness and let dry.

Kokiʻo ʻUla (Native Plant)

Kokiʻo is the Hawaiian name given to species of the native genus kokio, and ‘ula means red. The red native hibiscus was the Hawai’i state flower until 1988 when the native yellow hibiscus, maʻo hau hele, was chosen instead. The name Kokiʻo ʻula is shared by two species of native red hibiscuses: Hibiscus Clayi and Hibiscus Kokiʻo. There are several key differences between the two types: (1) Kokiʻo flowers can be red, yellow, and orange, while Clayi flowers are only red; (2) the Clayi leaves are smooth and toothed near the tip while the Kokiʻo leaves are toothed from the middle to the tip; and (3) Clayi hibiscus is native to Kauaʻi while Kokiʻo can be found on Molokaʻi, Oʻahu, Maui, and Hawaiʻi Island.

I used the Hibiscus Clayi for my dyeing but I can’t say where on Oʻahu I found the shrub. This species was discovered in 1928 by Albert W. Duvel and named for Horace F. Clay, a famous horticulturalist. Kokiʻo ʻula can be a shrub or a tree and the flowers bloom year-round. In ancient Hawai’i, the juice of the flowers was used to purify blood, leaves and buds were eaten for a laxative, seeds were given to weak children to strengthen them, and the bark was used for charcoal.

Supplies

- Kokiʻo ʻula flowers

- Cloth to dye

- Pot

- Bowl

- Strainer or colander

- Drying rack

Instructions

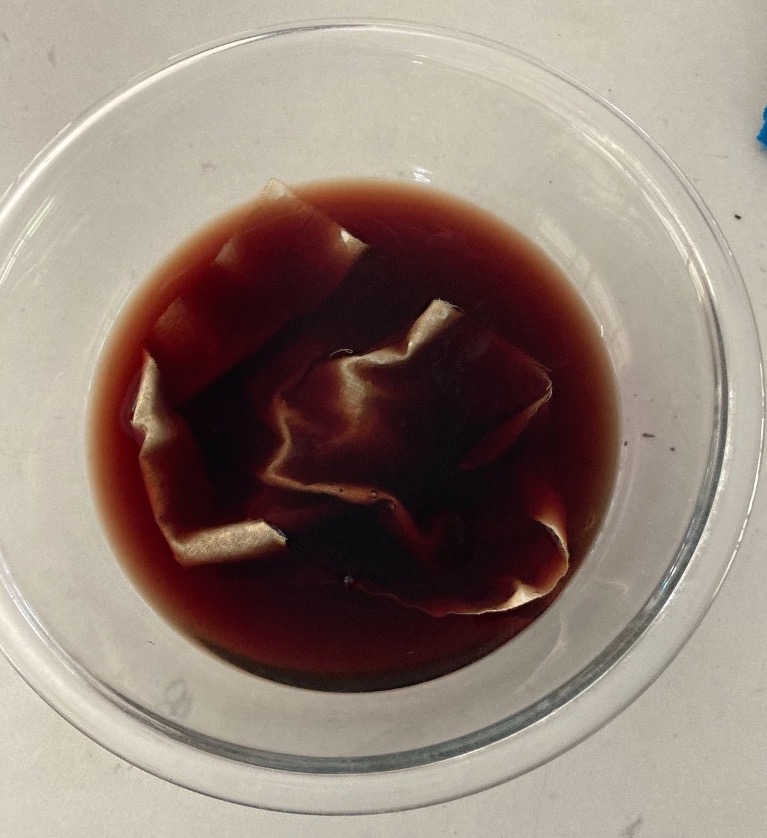

Gather flowers (I collected around 30).

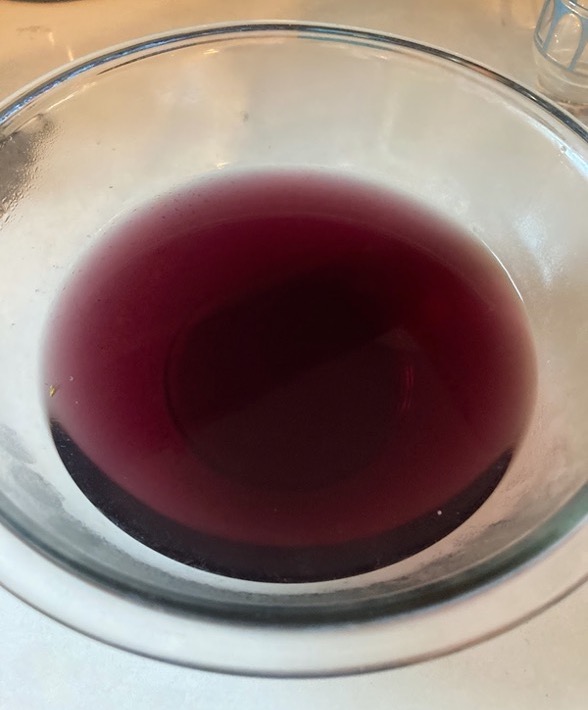

Put the flowers in a pot with one cup of water (or more, depending on the number of flowers). Bring to a boil and let sit until all the color from the flowers leeches out (flowers should turn a white grayish color).

Strain, making sure to press all the liquid from the flowers.

Submerge cloth in the dye. I let it sit for around 5+ hours to soak up all the dye. After the cloth is done soaking, run it under water to remove excess plant debris and dry.

Bonus Dye: Maʻo

I wasn’t planning on making more than three dyes, but Maʻo was available and I didn’t want to pass up the opportunity. Maʻo comes from the Hawaiian word ʻōmaʻo meaning green. It is also called ‘Huluhulu’ or ‘Hawaiian Cotton’. Maʻo is an endemic, endangered shrub not to be confused with maʻo hau hele which is a hibiscus. In ancient Hawai’i, the flowers, bark, and roots were used to treat stomachaches or to help with childbirth. Flowers were dried and eaten while its fibers were used as cotton swabs or stuffing for pillows.

Early Hawaiians used maʻo leaves to create a light green or red-brown dye, however, the color of these dyes didn’t last very long, fading after a few days. The flowers were used to make a yellow dye.

Instructions

Follow the same dyeing process used for hau and kokiʻo ʻula.

Special thanks to my mom and dad for driving me around, helping me collect plants, buying me muslin, and letting me make a mess of the kitchen. And also to Mānoa Heritage Center, Aunty Ke’ala, and Aunty Jenny for helping me and guiding me through the dyeing process. Thank you also to Aunty Talia for helping me find some of the plants.

References

Canoe plants of ancient Hawaiʻi: ʻOLENA. (n.d.). CANOE PLANTS OF ANCIENT HAWAII. https://www.canoeplants.com/olena.html

DeannaCat. (2020, April 27). How to make homemade dried turmeric powder ~ Homestead and CHILL. Homestead and Chill. https://homesteadandchill.com/how-to-make-turmeric-powder/

Hau lovely! (2016, June 26). Maui Travel Guide | Maui Nō Ka ʻOi Magazine | Maui Magazine. https://www.mauimagazine.net/hau-lovely/

Hau. (2011, May 6). Native Plants of Hawaii. https://dlnrnativegardenrestoration.wordpress.com/2011/05/02/hau/

Hawaiian native plants in Honolulu & oahu, Hawaii (HI) – Hui ku Maoli Ola native plant nursery. (n.d.). Native Hawaiian Plant Nursery Oahu HI | Habitat Restorations & Landscaping Services in Honolulu & Oahu, Hawaii (HI) – Hui Ku Maoli Ola Native Plant Nursery – Transforming Land Back To ‘Āina. https://hawaiiannativeplants.com/our-plants/

Hibiscus clayi — Kokiʻo ʻula. (n.d.). Hawaiian Forest. https://hawaiianforest.com/wp/hibiscus-clayi-koki%CA%BBo-%CA%BBula/

Hibiscus tiliaceus – Hau, sea hibiscus, beach hibiscus, mahoe – Hawaiian plants and tropical flowers. (n.d.). Wildlife of Hawaii. https://wildlifeofhawaii.com/flowers/1184/hibiscus-tiliaceus-hau/

History of turmeric | The history kitchen | PBS food. (2015, March 9). PBS Food. https://www.pbs.org/food/the-history-kitchen/turmeric-history/

Keala Wong/ Manoa Heritage Center, & Jenny Engle/ Manoa Heritage Center. (2018). Kapa Dye LOG.docx. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1sd_DXtz8nvk6IQLqhMvQcri9ASYFNHlFAoc17k_YlHg/edit?ts=5eab43a2

Koko Crater Botanical Gardens. (2020, May 5). HBG Koko crater. Government. https://www.honolulu.gov/parks/hbg/honolulu-botanical-gardens/182-site-dpr-cat/572-koko-crater-botanical-garden.html

Manoa Heritage Center. (n.d.). https://www.manoaheritagecenter.org/

A tale of turmeric (‘Olena). (2017, December 14). Hawaii Harvest Honey. https://www.hawaiiharvesthoney.com/a-tale-of-turmeric-olena/

Turmeric, the golden spice – Herbal medicine – NCBI bookshelf. (n.d.). National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92752/

University of Hawaii. (2009). Hibiscus clayi. Native Plants Hawaii. https://nativeplants.hawaii.edu/plant/view/Hibiscus_clayi

University of Hawaii. (n.d.). Hibiscus kokio subsp. kokio. Native Plants Hawaii. https://nativeplants.hawaii.edu/plant/view/Hibiscus_kokio_kokio

Hussey, L. (2018, November 14). The Sacred Process of Preparing Dyes with Hawaiian Endemic Plants to Use on Kapa – Hawaii Real Estate Market & Trends: Hawaii Life. Retrieved April 20, 2020, from https://www.hawaiilife.com/blog/sacred-process-preparing-dyes-hawaiian-plants/

Kapa Design Elements and Dyes. (2006). Retrieved April 19, 2020, from https://kapahawaii.com/hawaiian-kapa-designs-and-patterns.html

Magazine, M., & Ruppenthal, S. (2016, June 3). Hawaiian Dyes: Hawaiian Kapa: Hawaiian Color. Retrieved April 20, 2020, from https://www.mauimagazine.net/shades-of-the-past/

The Colors of Kapa. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://hawaiiantimemachine.blogspot.com/2010/11/colors-of-kapa.html

UNIT 15:Clothing, with Special Reference to Making, Decorating and Using Kapa. (n.d.). Retrieved April 19, 2020, from http://www.ulukau.org/elib/cgi-bin/library?e=d-0units-000Sec–11en-50-20-frameset-book–1-010escapewin&a=d&d=D0.17&toc=0

Love this post! What a fun project. Hope to try some of these one day. Lucky indeed to be surrounded by folks that know where all the good pickings for these plants are especially in such an urbanized place! I also wanted to share that ecology traditionally investigates the interactions between species and that when culture is part of the conversation surrounding plants that has historically been termed ethnobotany, a field that tends to get the short shrift (you are not a serious hard scientist like a botanist if ethnobotany is your jam). It may seem nitpicky to point this out but I hope it is helpful in navigating your interest in plants. Finding the lines between these and other disciplines has taken some research over the years but has helped me navigate scientific literature, be taken (more) seriously when communicating my ideas (I’m a minority woman so I’m afraid being taken seriously in white male dominated fields like much of the sciences is an uphill battle), and understand the conversation in this arena at greater depth.